The King of Pandhandlers

Jim Thompson wraps his arms around his smiling friend Colin Collins as they hold their beer cans up to the camera. It’s a good day for a cool beverage.

The temperature hovers around 95 degrees near Julia Davis Park in Boise, Idaho. It’s early in the day, but this is not the first beer of the day for Thompson and Collins, two homeless men living on the streets of Boise.

They’ve been friends for the past two years and have endured many cold nights living in Thompson’s broken-down Chrysler New Yorker. The two have worked together around the city doing odd jobs, like when roofing and landscaping companies hire them as day laborers. Thompson and Collins have become a common sight together, panhandling on the corner of Main and 6th streets in downtown Boise panhandling. “I’m the king of panhandlers,” said Thompson, who hides behind a full beard. “No one can out panhandle me.”

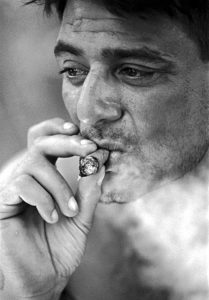

Thompson and Collins are among an estimated 600 homeless population who call the streets and park benches of the Idaho capital their home (Note: Today, unlike when I shot this feature in 1998, the number is far higher. Thompson, who often wears a Chicago Cubs cap and dark sunglasses, came to Boise in 1998. Like many others, his downward spiral started after a DUI.

“It ruined my life,” said the 43-year-old Thompson, who has had several DUIs. He comes from a large family where both parents drank heavily. He began when he was 12. “I’m an alcoholic,” he admits.

Collins arrived in Boise shortly after his friend did. A tall and lanky 30-year-old with missing front teeth, Collins had a promising career working for the U.S. Forest Service in Challis, Idaho, until he was pulled over one morning and arrested for DUI.

“After partying all night, I blew a .24,” he recalls. He served 120 days in an Idaho Falls prison before coming to Boise in August 1997. Collins also comes from a family of alcoholics. His father died at age 54 of cirrhosis of the liver. “I was crushed. He was my best friend.” Since then, Collins has battled alcohol abuse for 20 years. “I don’t want to follow in my dad’s footsteps.

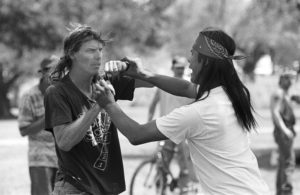

Circle of Stones

Thompson and Collins’ story is not unique. Alcoholism is a defining factor in many homeless communities across the country. In many cases, substance abuse has resulted in tragedy.

In January 1997, Joseph Jimmie Johnson, 60, was found frozen to death after a night of drinking in Boise’s Ann Morrison Park. Johnson, a Native American who went by the street name of Skywalker, lived along the Boise River for several summers.

After he died, friends turned out for a memorial near the bench where his body was found. A circle of stones was placed on the ground nearby. In the center was a bottle of Jack Daniels whiskey, a pack of Camel cigarettes, and a disposable lighter.

“He was my friend,” cries Robert Qualls, who was among a handful of homeless people and community advocates who came to the memorial. Many of the homeless men began drinking from the whiskey bottle. Soon, several were too drunk to stand and had to be carried away sobbing.

“He taught me about nature — and about myself,” says Qualls.

A Cast of Characters

Boise’s homeless world is filled with fights, miserable cold nights, and a never-ending search for a drink. Thompson and Collins have a lot of company. These friends go by names like Mooncritter, Cigarette Bob, Rocky, and LaDonna. These are just a few of the many characters who come in and out of their lives.

“We drink from the time we get up until we go to bed,” says LaDonna, as she sits surrounded by men on a park bench with Boise’s skyline in the background.

Sitting next to her is Rocky Burkett. Burkett, a homeless veteran, would later end up in Boise’s VA Hospital after suffering a heart attack. “We were drinking all day. He hadn’t had anything to eat for days,” she says. Burkett would enter a 21-day detox program. “After I go through this, I get my job back,” said Burkett after his release from the hospital.

Steve Downey, a counselor at Boise’s Community House, a homeless shelter, has seen his share of homeless men and women in hospital beds. He’s been able to help some, while he has watched others die. Downey recounts trying to help Napoleon, a homeless man suffering from cirrhosis of the liver.

“I saw him before he died. His skin was as yellow as anything I’ve ever seen,” says Downey, who himself is a recovering alcoholic. “Steve, I don’t look that bad do I?” he remembers Napoleon asking him. “Yeah Napoleon, you do look that bad,” he answered. Napoleon died at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center three days later.

“Cigarette Bob” Allman is another homeless veteran who ended up in a hospital. Allman was rushed to the hospital after suffering from seizures and collapsing in the park. “I don’t remember a thing,” he says. “I wasn’t drinking.”

“A drinker robs their body of all vitamins,” said Downey. “You just lie there. You twitch and shake.”

Downey believes the doctors are not doing their part to stop the vicious cycle of alcohol abuse among the homeless. “The medical profession never lists the cause of death as alcoholism,” he said.

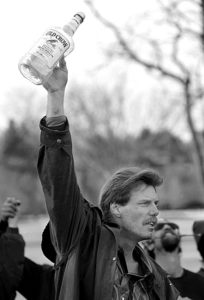

A Never Ending Dream

It was a cool and crisp October day. The fall leaves are starting to turn. Ducks splash in the nearby Ann Morrison Park boat pond and Jim Thompson is dreaming of a better life.

In Thompson’s dream, he’d like to trade places with a man who has a nice home with a white picket fence and a beautiful wife. This is his dream for the next few years, he says. He occasional sips from a bottle of vodka he pulls from his green army surplus jacket.

Thompson knows he’s got problems. He has seen several friends die, and many overdose. He understands this is the way it is when you live on the streets: Your friends come and go.

At this moment his daydream ends. He realizes his mistakes. “It’s ruined my life,” he said, holding up his bottle. “I’ve got nothing.”

The images and notes for this story were produced between 1998-1999 in Boise, Idaho. Most of the people in this article have left town and I’ve never seen them again. As of production of this work I’ve not seen Jim Thompson. Though I’ve seen and spoken to Colin Collins several times, unfortunately Collins is still homeless and panhandling — but without the King of Panhandlers by his side.